Discover how online shopping is reshaping the retail landscape and consumer behavior worldwide.

Tuesday, February 25, 2025

A Style All His Own

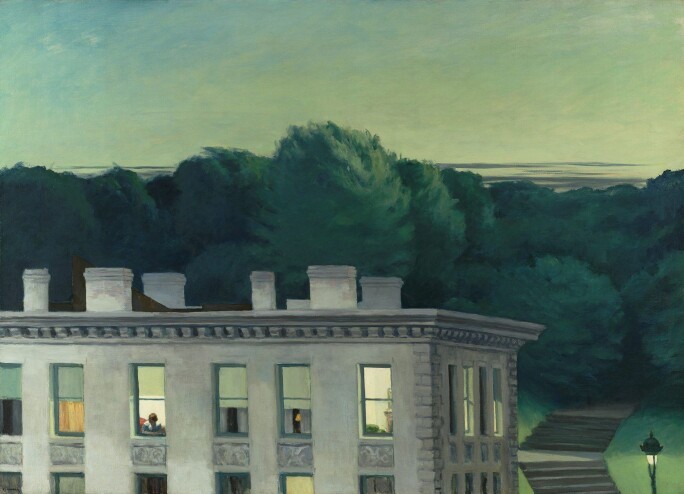

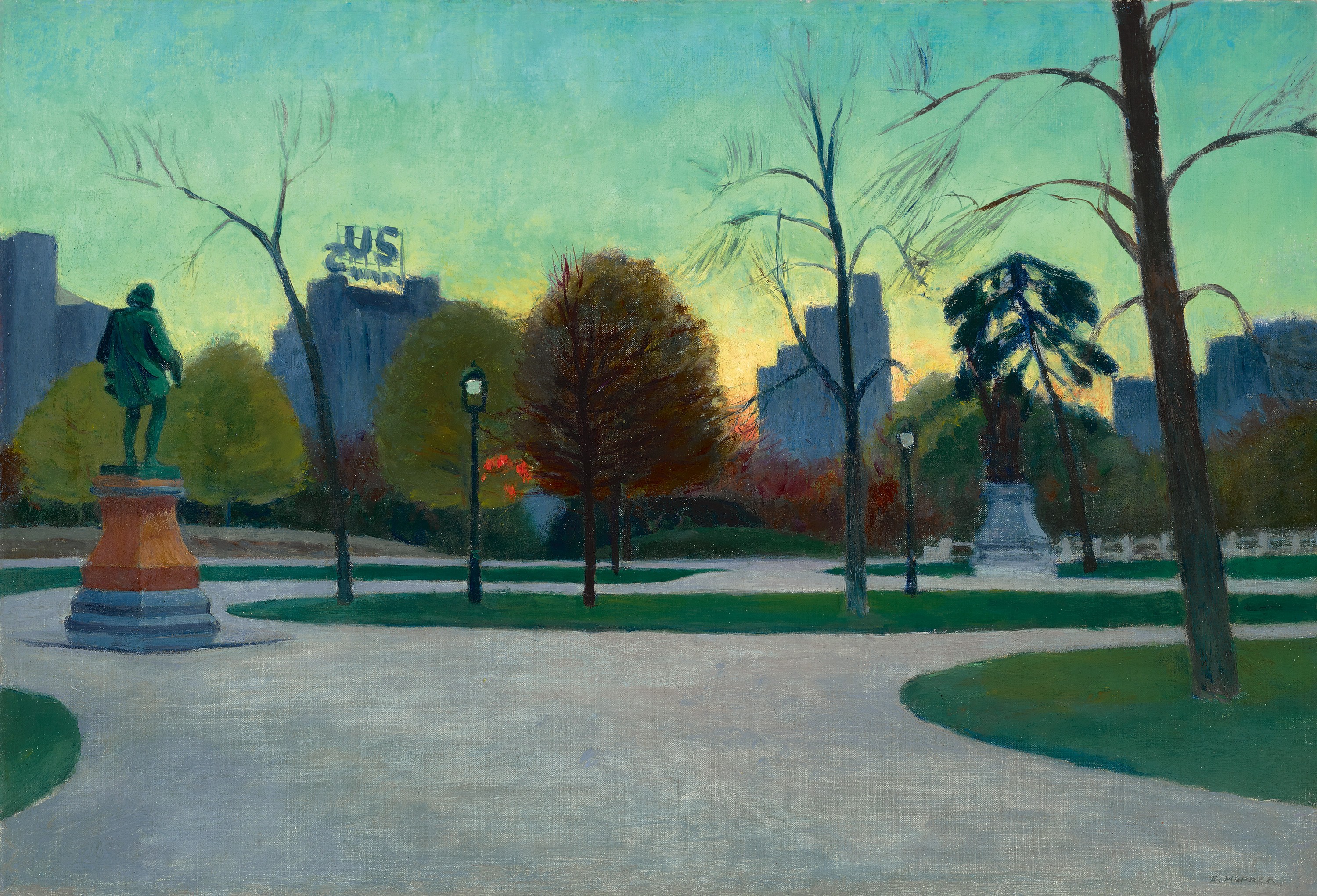

Hopper's artistic vocabulary was deceptively simple. He painted ordinary places—cafeterias, gas stations, office buildings, the anonymous architecture of mid-century America—yet somehow transformed them into stages for existential drama. His genius lay not in technical virtuosity or avant-garde experimentation, but in an almost supernatural ability to distill atmosphere. Light was his primary tool: harsh afternoon sun streaming through venetian blinds, the sickly fluorescence of all-night establishments, the golden hour glow that makes everything feel both beautiful and transient.

Where his contemporaries were embracing abstraction and European modernism, Hopper remained stubbornly committed to realism, though his realism was anything but photographic. He stripped away the extraneous, leaving only what was essential to convey a mood. The result was a kind of hyperreality—scenes that feel more like the atmosphere of a memory than an actual place. His compositions have an almost cinematic quality, as if we're glimpsing a single frame from a film noir, frozen just before or after something significant has happened.

The figures in Hopper's paintings are perhaps his most haunting element. They rarely interact. They stare out windows, sit alone at counters, or share space with others while remaining utterly disconnected. Even in "Nighthawks," his most famous work, the four people in the diner exist in what feels like separate psychological universes. This wasn't mere stylistic choice—it was Hopper's clear-eyed observation of modern urban life, painted decades before terms like "alienation" and "anomie" became cultural buzzwords.

The Man Behind the Canvas

Edward Hopper was, by most accounts, as enigmatic and solitary as his paintings suggest. Born in 1882 in Nyack, New York, he was a man of few words who seemed to prefer observation to conversation. His wife, Josephine Nivison, was also a painter, though she largely sacrificed her own career to manage his. Their marriage was reportedly tempestuous—she was vivacious and social; he was withdrawn and taciturn. Yet she served as the model for virtually every female figure in his work, her body and presence appearing again and again in those isolated rooms and empty streets.

Hopper was notoriously slow and deliberate. He might spend months working on a single painting, not because of technical difficulty, but because he was waiting for the right moment, the right feeling. He rejected the idea that he was painting loneliness or alienation, insisting he was simply painting light and architecture. Yet this denial itself feels very Hopper—a man uncomfortable with emotional display, insisting on the technical and observable while creating work that pulses with unspoken feeling.

He was also remarkably resistant to interpretation. When pressed about the meaning of his work, he would deflect or offer vague, unsatisfying answers. "If I could say it in words," he famously remarked, "there would be no reason to paint." This reticence was part stubbornness and part genuine philosophy. Hopper believed paintings should speak for themselves, that over-explanation diminished their power.

The Legacy

What makes Hopper's work so enduring is its universality. He painted specifically American scenes—the diners and motels and brownstones of mid-century life—yet the emotions they evoke transcend time and place. His paintings capture something essential about the human condition: the way we can feel most alone when surrounded by others, the melancholy beauty of ordinary moments, the sense that we're all bit players in some larger, unknowable narrative.

In our current age of digital connection and curated social lives, Hopper's vision feels more relevant than ever. His paintings remind us that loneliness isn't a bug in the system of modern life—it's a feature. They suggest that isolation might not be something to fix, but something to observe, to sit with, perhaps even to find strange beauty in.

Edward Hopper died in 1984, having spent his final years in the same Washington Square studio where he'd worked for decades. He never courted celebrity, never created manifestos or artistic movements. He simply painted what he saw, or rather, what he felt when he looked at the world around him. That this quiet, taciturn man created some of the most emotionally powerful images in American art history is perhaps the greatest testament to the power of careful observation and patient craft.

His paintings hang in museums now, iconic images reproduced on everything from posters to coffee mugs. But they lose nothing in familiarity. Look at a Hopper long enough, and you'll still feel it—that particular ache of being alone in a crowd, of light falling just so through a window, of waiting for something you can't quite name. In capturing that feeling so precisely, Hopper didn't just document American life—he revealed something true about all of us.